A Brief History of Trading Technology

There was a time when high-frequency trading meant owning a pigeon.

When it comes to successful trading, having the best technology available can make all the difference in the world. Today that means fast internet connections, high-speed computers, and lightning-fast quotes and executions.

But once upon a time, the best technological advantage a trader could have was owning a telescope.

Amsterdam is famous for many things, not least of which are past residents like Rembrandt, Van Gough, and brothers Alexander Arthur and Edward Lodewijk, who, after relocating to Pasadena, California, went on to form a little band known as Van Halen.

But in financial circles, this quaint Dutch seaside town’s fame comes from being the birthplace of the modern stock exchange.

Though regional markets in Europe had existed for centuries, most were based around commodities like wheat, gold, and livestock, and very few transactions were done in the forerunner of what we now call a share of stock.

The Amsterdam Exchange, founded in 1602 by the Dutch East India Company, changed that by offering printed stocks and bonds on the secondary market, which were traded alongside commodities.

When the invention of the telescope was patented in 1608 by its creator, Dutch resident Hans Libbershey, the idea was to use it to look towards the stars. But technology-minded traders at the Amsterdam Exchange had other ideas.

These speculators found that if you knew ahead of time what cargo a merchant ship was scheduled to carry, you could use the telescope to your advantage.

Willy traders would position watchmen on the shores of the Port of Amsterdam, scouring the horizon for the first signs of incoming ships. Once spotted, they could estimate how much of a certain commodity a ship held by how low it rode in the water.

More of that commodity meant higher supply and lower prices. And the opposite meant higher prices.

With those estimates in hand, couriers would then race to the exchange floor and update the traders with this “inside” information, allowing them to place buy and sell orders hours ahead of their competitors.

As equity investing became more popular, stock exchanges began to pop up all over the world, including the New York Stock Exchange in 1792, the London Stock Exchange in 1801, and the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 1878.

The proliferation of exchanges necessitated the creation of new technologies in order to deal with the increased trade volume and the distance over which information was transmitted.

This new technology often took unusual forms.

For example, in parts of Europe, during the first part of the 19th century, homing pigeons were used to “transmit” quotes, news, and other market data between exchanges. This experiment ultimately failed, but the company that tried it ended up doing just fine.

You may have heard of them. They’re called Reuters.

By the mid-1800s in New York, technology took the form of young, athletic men who would sprint from the exchange floor to brokerage offices around the city, delivering the latest quotes. These quotes would then be posted on chalkboards and displayed in the window or lobby for the public to see.

The New York Stock Exchange, just one of many regional exchanges at the time, had the largest chalkboard, which is why it became known as “The Big Board.”

The job of posting quotes was an entry-level job for aspiring traders who could easily be identified by the fur sleeves they wore so that they didn’t accidentally erase a quote.

With the founding of the New York Times in 1851, daily newspapers became a more efficient way to distribute timely news to the masses, but it wasn’t until 1889 that the first edition of the Wall Street Journal appeared, which contained not only market news, but index quotes as well as select individual stock quotes. The Times added their own stock quote table not long after.

But by that time, among financial professionals, the quest for faster data flow had already taken a quantum leap forward with the introduction of a stunning technological advancement - the ticker tape.

The telegraphic printing system had been around since 1854 but suffered from various design flaws, some of which were mechanical – like its hand-cranked operation – and some of which were operational – like only printing in Morse code.

These flaws made it impractical for stock quotes and it wasn’t until 1867 that Edward Calahan unveiled the first stock ticker system, aka, the ticker tape.

The introduction of the ticker tape was as revolutionary to Wall Street at the time as the advent of the internet would be over 100 years later, a point illustrated best by the story of “The American Deer” from Michael Kemp’s book, Uncommon Sense: Investment Wisdom Since the Stock Market’s Dawn.

One of the most celebrated of Wall Street’s messengers was William Heath, better known as ‘The American Deer’.

If Heath were alive today, he’d likely be an Olympian.

Six foot six inches tall, gaunt and angular with a prodigious drooping mustache, he cut a conspicuous figure on Broad and Wall Street as he raced between the Exchange floor and the brokerage houses.

According to an article in the New York Times, he was ‘as quick in his locomotion as in his operation.’

But Heath’s speed was eventually displaced by technology.

In late 1867, the first stock ticker, invented by Edward A. Calahan, was placed in the office of broker David Groesbeck & Co.

Even within the parameters of the financial district, the superior speed delivered by the electric impulse supplanted that previously delivered by human muscle.

When this new stock ticker was installed, the Groesbeck brokers gathered around in amazement. This quickly changed to amusement at Health’s expense as Wall Street’s fastest messenger burst into their office.

In his panting voice, he reeled off the prices of recent trades on the stock market floor.

But he was too late.

The ticker tape bearing the same information had already spewed from the stock ticker onto the office floor.

Though Calahan’s was the first practical ticker tape, it wasn’t until Thomas Edison invented the Universal Stock Ticker in 1869 that it began to receive wider acceptance in the financial world.

Edison’s ticker printed out an alphanumeric code on a thin strip of paper – the “tape” – at a speed of one character per second. The names of companies were cumbersome and time-consuming to input, so they were abbreviated in an early form of what we now call a stock symbol.

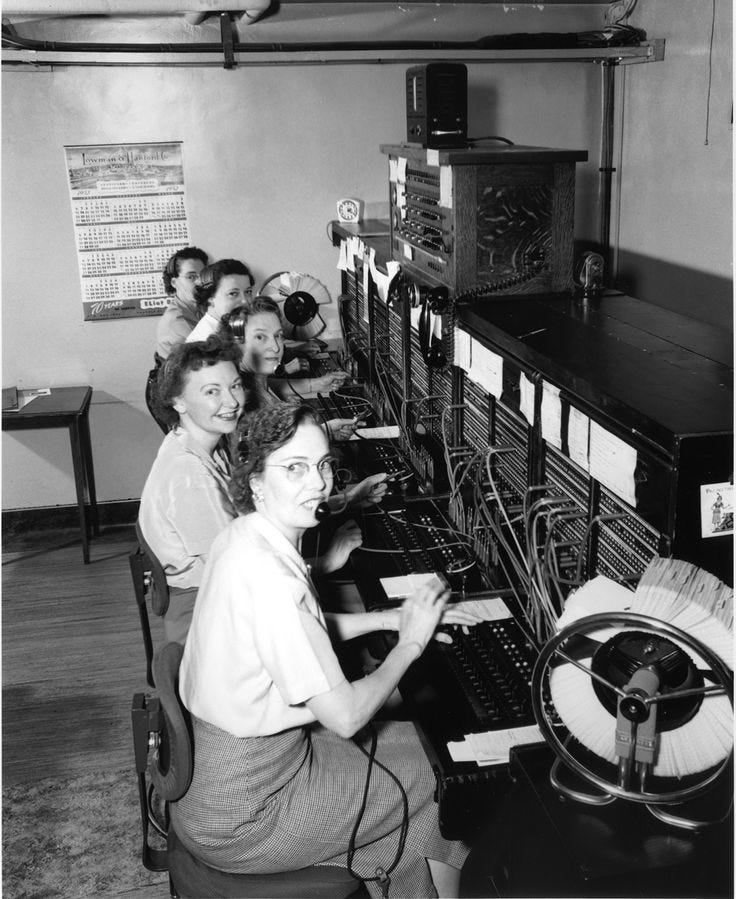

Ticker tape machines became the stalwart technology on Wall Street for transmitting quote data over long distances, but even as newer and more advanced models became available in the early 1930s, by the 1950s, there was still a huge efficiency gap in the process.

This was partly due to the fact that despite being able to transmit single quotes extremely fast, the “pipeline” of the ticker tape was extremely narrow.

As trade volume increased, it became more difficult for the tape to stay current since keyboard operators could only enter one quote at a time and the machines on the receiving end could only print one quote at a time.

The other problem was display. As individual quotes came in on the ticker, they still had to be transferred to a format large enough to display multiple tickers and to allow brokers, or the public, to read them.

And in 1950, that format was still often the chalkboard.

To give you a sense of how slowly things worked back then, let’s take a look at a process that most of us take for granted these days, buying a stock.

If you wanted to buy a stock in 1950 you had two choices; you could call your broker or you could visit their office.

Calling presented a number of issues in and of itself. First off, not every house had a phone in 1950. And if you did have one, you had to hope that the single line at your broker’s office was free when you called.

But more importantly, unless you were a well-known customer of your brokerage – having bought or sold stocks on a regular basis – they would not take a phone order for fear of non-payment.

In addition, trading stocks was still a very foreign concept to most Americans, and as with most financial transactions at that time, it was preferred to be done in person.

After arriving at your broker’s office, you would need to know the current price of the stock you wanted to trade, which hopefully was up on their board. But if the price was old, or your stock wasn’t on the board, or there was no board at all, the broker had to telegraph a quote request to the firm’s “wire room” in New York.

That request was then phoned to the exchange where a messenger would walk to the part of the floor where the stock was traded, copy down the price, walk back to his post, call the wire room with the price, who would then telegraph the quote back to your broker’s office. This process could easily take 30 minutes or more.

[Note: You might wonder why the broker didn’t just call New York directly for the quote? Well, in addition to the previously noted limitations of the 1950’s era phone system, back then there was no direct access to the exchange for brokers. Also, a long-distance call between Los Angeles and New York, for example, ran about $39.00 for 5 minutes.]

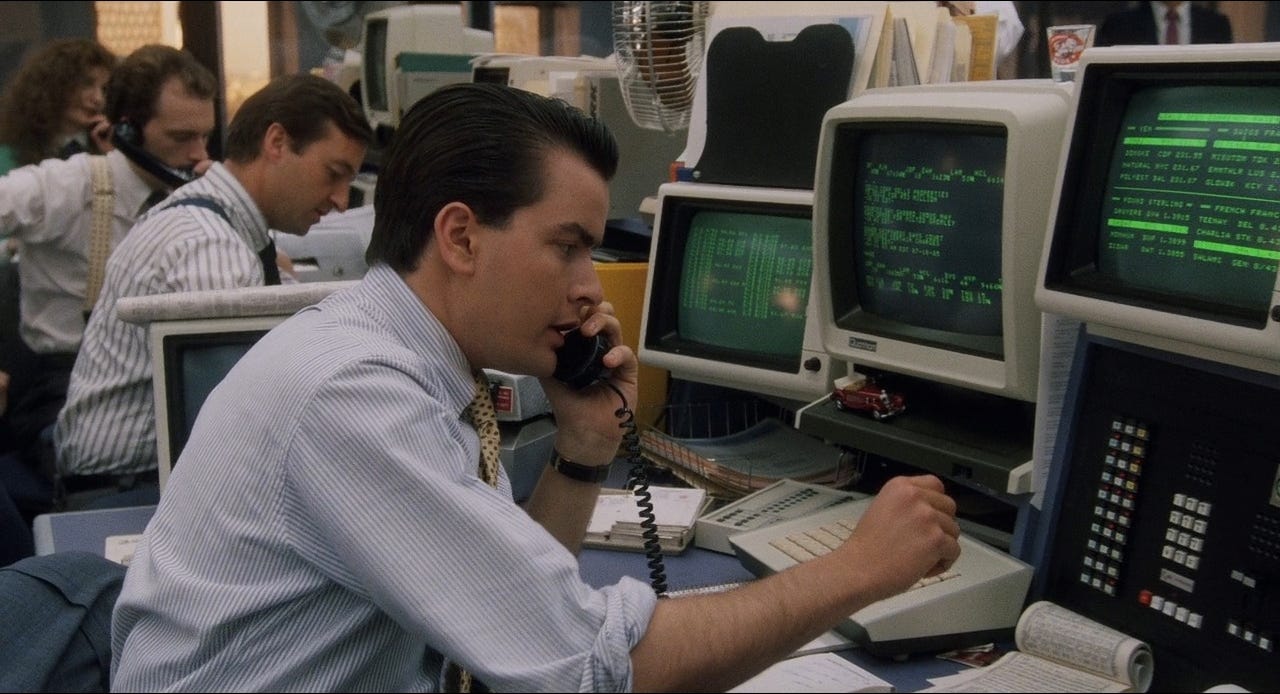

Fortunately, another technological advance was right around the corner with the introduction of the Quotron.

The Quotron used magnetic tape to store the quote data coming in from the wires. Then a broker, or broker’s assistant, could just punch in a symbol and immediately pull up that last quote for almost any stock.

The Quotron was an instant hit when introduced in 1960, and by 1961 there were over 800 of them installed in brokers’ offices across the country.

This new, faster access to data made automated quotation boards – which had been around since 1929 – a viable way to display dynamic quotes, and by 1964, 650 brokerages offered them.

But it wasn’t until 1971, when the National Association of Securities Dealers created the first all-electronic quote exchange, that a technology was launched that most of today’s market participants will recognize.

The National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations, or NASDAQ for short, was originally only designed as a quotes system, with no trade taking place.

The NASDAQ helped provide investors with more transparent pricing by showing stock quotes not normally reported, which narrowed the spread - the gap between the bid and ask price – on many stocks.

Eventually, NASDAQ began taking over the over-the-counter trades – trades done between two parties without an exchange – and has grown to be a world-class exchange with over 3,00 listed stocks that trade roughly 2 billion shares daily.

Today it is the second-largest stock exchange in the world behind the New York Stock Exchange.

Make sure to check out the latest episode of the new Lund Loop Podcast.